A leaf curling up, buds sticking together, ants climbing up a stem in single file… Aphids are often there long before we can see them clearly. And because they multiply so quickly, in just a few days we can go from a simple outbreak to an infestation that weakens roses, vegetables, shrubs and young fruit trees.

The good news is that you can almost always regain control without chemical insecticides, as long as you spot early, break the ant-aphid “pairing”, and encourage the right beneficials at the right time.

How to recognize aphids (even when you can’t see them right away)

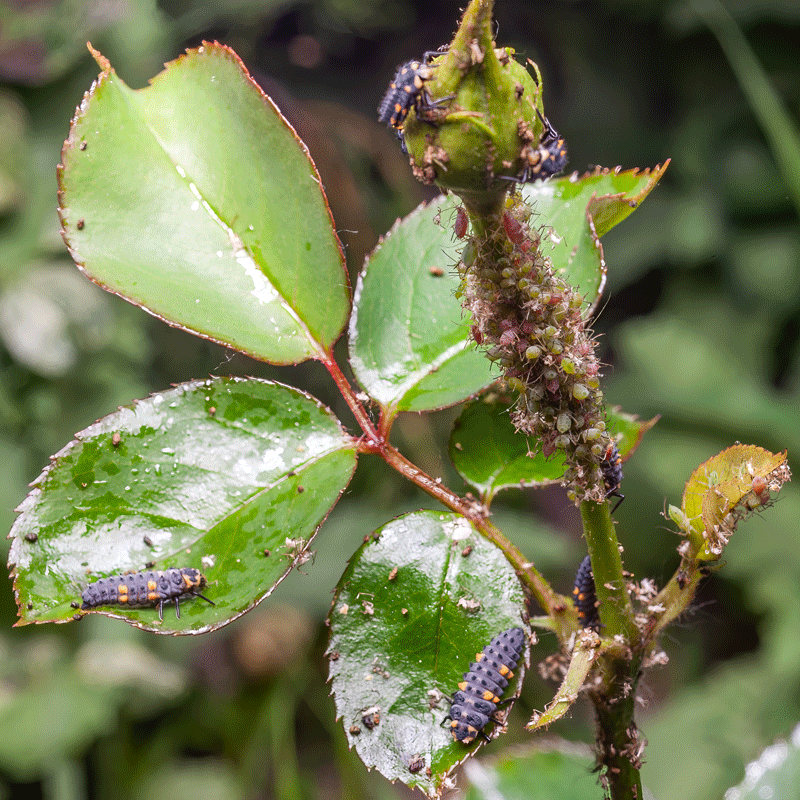

Aphids are generally only a few millimeters long. They gather in colonies, often :

- on young shoots (tender stems, growth tips)

- on buds (flower or leaf)

- under leaves, sheltered (but not protected from ladybugs)

The signs that don’t deceive

Even if you can’t make out the insects yet, three clues come up very often:

- Leaves are sticky

Aphids take up a lot of sap and reject the excess in the form of honeydew, a sweet, sticky substance.

- Black spots appear on the leaves

Honeydew favours a black fungus, fumagine, which interferes with photosynthesis.

- Ants come and go on the plant

When ants move up and down a stem, there’s often a reason: they’ve come to “collect” the honeydew on which they feed.

Plants most prone to aphid infestations

Unsurprisingly, certain plants attract aphids more quickly: roses, beans, cabbage, cucumbers, as well as many shrubs and fruit trees (e.g. apples).

Why aphids weaken your plants so much

Aphids sting tissues and pump sap. On a young or growing plant, this can lead to :

- Deformed, curled or twisted leaves

- Slower growth and weaker stems

- Buds abort and flowering is disrupted

- Smaller, sometimes deformed fruit

Another important point is that some aphid species can transmit viruses from one plant to another. In a vegetable garden or nursery context, this is one of the reasons why early intervention is preferred.

Ants and aphids: why this association must be broken

Ants are not the “cause” of aphids, but they can turn a limited outbreak into a persistent problem. They often protect colonies from natural predators to preserve their honeydew source.

Simply put: as long as ants have access to the plant, natural regulation is much less effective.

How to prevent ants from defending aphids

- On trees and shrubs with trunks : place sticky strips around the trunk in spring, high enough to avoid dirt and bridges (weeds, stakes).

- On roses, small fruit trees and multi-stemmed shrubs, the use of a sticky tape is often less practical. In this case, the aim is above all to reduce access (surveillance + targeted actions) and to favor a “prevention + beneficials” strategy as soon as the first outbreaks appear.

- In vegetable gardens, dense beds or greenhouses: watch for ant trails, limit shelter (boards, very dry areas), and act as early as possible on the first aphid outbreaks: the longer you wait, the more the “pantry” effect sets in.

Prevent infestations: 6 simple reflexes that make a real difference

Prevention doesn’t require a “perfect” garden. It’s all about making your plants less attractive, and your garden more hospitable to beneficial insects.

1) Avoid nitrogen excesses

Too much nitrogen makes the sap more “nutritious” and may attract more aphids. Prefer :

- Mature compost

- Balanced, time-release fertilizers

- Moderate inputs, adapted to the plant

2) Monitor early (and short)

In high-risk periods (spring, early summer), a quick visual check 1 or 2 times a week is often enough. The aim is not to inspect everything, but to take a look at a few key areas:

- Rod ends

- The underside of young leaves

- Flower buds

3) Promoting useful biodiversity

Syrphid beetles, lacewings, ladybugs, insectivorous birds… a diverse garden defends itself better. Here are a few ideas:

- Sow melliferous flowers throughout the season

- Leave some corners “a little wild

- Preserve hedges and refuges

- Install insect hotels (useful, but not magical: it’s the whole package that counts).

4) Use “buffer” or “decoy” plants

A well-known example: nasturtiums easily attract aphids. The idea is to concentrate pressure on a controllable area.

5) Limiting water stress

A stressed plant (lack of water, jolts) reacts less well. Regular watering and mulching can help maintain more stable growth.

6) Act when the first outbreak occurs, not when “everything sticks”.

This is THE point that changes everything. When colonies become very dense, you often need to combine several actions (shower + auxiliaries + ant management).

What to do in case of infestation: a simple step-by-step method

Step 1: Reduce the colony without “sterilizing” everything

Objective: lower the pressure to give the plant air.

- Water spray on roses, broad beans and solid stems: very effective in dislodging aphids.

- Black soap (diluted) or nettle purin-type preparations: useful for support, especially at the start of an attack.

Avoid “indiscriminate” treatments, which also affect beneficials already present.

Step 2: install natural regulation (ladybugs / larvae)

Ladybugs are among the biggest predators of aphids. Key point: the larvae are often the most voracious and remain on the plant on which they have been deposited, while the adults can fly away.

- An adult can consume up to 50 aphids a day

- A larva can carry up to 150 aphids a day

At Horpi, the species we have selected isAdalia bipunctataa ladybug endemic to Europe, with a well-documented life cycle (egg → larva → pupa → adult).

Step 3: A successful introduction

A few simple, practical rules:

- Introduce larvae at the right time: at the first outbreaks, before the plant is covered with aphids.

- Avoid periods of heavy rain, wind, cold or frost.

- Introduce at the end of the day (less light, less stress).

- Place larvae and/or adult ladybugs as close as possible to the colonies.

- Do not introduce on a plant recently treated with a chemical insecticide (allow a delay of one to two weeks).

- And above all: if the ants are very active, reduce their access, otherwise efficiency will drop.

How many larvae do you need?

Requirements vary according to plant and level of infestation. As a guide, there are introduction guidelines for each type of plant:

| Plant / area | Larvae marker |

| Roses | 5 to 10 larvae per rose |

| Ornamental shrubs | 5 to 10 larvae per shrub |

| Hedges | 20 to 50 larvae per m². |

| Small fruit trees (currants, etc.) | 5 to 10 larvae per shrub |

| Low-stemmed fruit tree | 20 to 40 larvae per tree |

| Vegetable garden / greenhouse / flowering plants | 2 to 5 larvae per plant (or 10 to 20 larvae per m² in infested areas) |

The idea is not to “overdose”, but to aim just right: targeted households + favorable conditions + follow-up.

Follow-up: what to expect and when to intervene

After introduction, population decline can take up to two weeks, depending on initial intensity. In the case of heavy infestations, a second course of action may be useful (e.g., a new introduction or a combination with spray cleaning).

Reading tip: if you observe “mummified” aphids (small brown/black hulls), this is often a sign that other beneficials (parasitoids) are already at work. In this case, avoid aggressive treatments which break this dynamic.

To sum up: the best strategy against aphids is to start early.

To avoid chasing aphids all spring:

- Spot early (sticky leaves, ants, young shoots)

- Avoid excess nitrogen

- Reduce the “guard ant” effect

- Act locally (water jet / mild solutions)

- Install natural regulation (larvae and/or adults) at the right time

A living garden is not a garden without insects. It’s a balanced garden, where aphids don’t have time to become a problem.